The Last Taboo – Why It's Time To Break It

When I saw someone drop down dead - no one seemed capable of dealing with what happened. Death is frightening - but we need to face it.

I was sixteen when I saw my first corpse. It wasn’t the made-up-and-manicured, hands-clasped-in-coffin sort of body - but raw and somehow much more real.

A man I had met just hours before seemed to deflate like a hot air balloon, collapsing on the ground in front of me. My clearest memory is staring at him suddenly rigid and still and thinking he had forgotten how to breathe: silent for a prolonged period – then sucking in a vast and rasping breath before falling silent again. This happened a few times, before another, final sound that proved to me that there is no dignity in death.

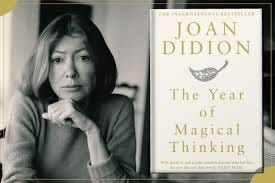

Joan Didion opens her grief memoir, “The Year of Magical Thinking” with the first words she wrote after her husband’s death:

“Life changes fast,

Life changes in an instant.

You sit down to dinner and life as you know it ends.”

She’s right. Life changes in an instant for the dead and the ones they leave behind. A person is here – and then they are not. We have become masters of avoiding that central truth.

Earlier that morning, with a teenager’s certainty and lack of experience, I had decided to believe something I’d actually misunderstood. I was told in Scandinavian countries they don’t wear thick clothing, preferring several thin layers. I concluded this would be the sensible thing to do climbing Ben Vorlich – one of Scotland’s Munros, or mountains over 3000 feet.

The rest of the party looked quizzically at me as I turned up in a body warmer over a light sweatshirt and two t-shirts. I must have looked hopelessly under-dressed – but no one challenged me.

Leading the way was Ken Stewart, a consultant obstetrician. The rest of the party was made up of his son – and my friend – Murray, and a man called John Bennett. Again, I was a typical teenager - polite, but not really engaging much with a man who was a stranger to me.

As we settled in for the drive, there was some stilted conversation about what had happened at Christmas and plans for New Year. Ken drove a white Lada estate, which he proudly asserted was, “The cheapest car, and the best!” Murray and I sat in the back and with the gross, judgmental attitude common in teenagers, rolled our eyes and making coded remarks about the chat in the front.

The sky was clear at the foot of Ben Vorlich, with no hint of the snowstorm that was heading our way. None of us seemed to have checked the weather forecast. The icy gravel crackled and spat like hot fat in a pan as we parked and started our ascent.

The climb to the peak was hard going, but little of note happened. The well-trodden paths were hard, with large patches of milky ice. The final ascent was steep and slippery. Breathless, I noticed the sky was beginning to darken. We had barely stopped at the cairn when the snowstorm hit. Not soft, fluffy flakes, but sharp and spiky, almost hail. They stung as they hit our skin. We had to shout to be heard and Ken suggested that we huddle together until it passed.

I curled up, almost completely exposed to the elements, with only a vague sense of the others next to me. The storm was so intense I could barely see the hand in front of my face. It was like being stuck in a television set tuned to static and the volume turned up to the max. I have no idea how long we were there. It felt like hours. But it may have been much shorter. Then, as quickly as it had come, the storm was over.

We had to descend – but the paths had been covered and the route wasn’t clear. Ken suggested we “glacade” which he explained was more commonly known as “arse-ading” – sliding down on your backside.

I took the lead. It was slow progress. Sometimes the ground was rough. Sometimes smooth – and you could slip easily. This happened to Ken. I suddenly felt his boot in my back with his full weight behind it. It was enough to give me booster rockets and I shot forward and lost control. The mountain became a giant slide and I spun one hundred and eighty degrees, watching the rest of the party disappear into the distance. I then tumbled head over heels. The cliché about everything going into slow motion is true. I have no idea how long it lasted, but I felt like I was falling forever. I still dream about it.

I tried to do anything to get a grip and slow myself down. Fingertips. Tensed muscles. Finally, heels digging in. I stopped with a jolt, working out if I’d been injured. My heart rate must have trebled. Adrenaline was shooting through my veins. My mind fizzed - my vision blurred for a few seconds before settling. I was scratched and bruised – but as far as I could tell, there was nothing broken.

When the rest of the party caught up with me Ken said, “That looked fun!” I wanted to shout at him, “That wasn’t fun, you fucking idiot!” but I kept it buttoned.

We must have eaten or drunk something – but I don’t remember. The ground was less steep here and instead we agreed to form a line and march back to the car.

I was last in line this time – lamenting the fact that I had agreed to come, aching and grumpy that I could have stayed in bed. John Bennett was just ahead of me. His dark hair seemed wet, and he struck me as heavy-footed and deliberate, suddenly stepping left or right, then correcting it with a giant stride. He looked loose, almost springy. Drunk maybe? But I concluded this was just how he walked.

Then something strange happened. He took off his rucksack and clasped it in his arms. I stopped to let him carry out the manoeuvre, noticing Murray and Ken were getting further ahead. He started walking for a while. Then he stopped and pulled a lunch box out of the rucksack and let it drop to the floor, before carrying on walking. I picked it up and called after him, but he ignored me. We walked a little more, then the pattern was repeated, this time discarding some waterproofs, which I also picked up. Next, he poured the water out of his bottle before seeming to think better of it and casting it aside. Finally, he dropped expensive binoculars which were still in their case. I picked them up again. By now my arms were full and I was starting to worry: Why was he doing this? Why wasn’t he responding?

I called ahead to the others, “Stop! You need to stop!” They looked back, confused, “It’s John…he keeps dropping his things.”

It took a few seconds for them to make their way back to us. We stood in a circle. John seemed delirious. I tried to explain what was going on.

The others looked worried, “Why are you dropping things, John?” Then it happened. The hot air balloon deflating. The forgetting how to breathe. The sound of his bowels loosening. I made my way over to Ken, who was a doctor, “What’s happening? What’s wrong?”

He answered, straight and to the point, not softening the blow, “I think he’s dying.”

I may not have said the words, but my reaction was, “Wait. What?” This made no sense. People didn’t just keel over and die in front of you. Certainly not in the UK. Something would happen. He would be saved.

These were the days before mobile phones, and it was agreed that Murray and I would get down Ben Vorlich as quickly as possible. We didn’t question the wisdom of this. John was surely dead. The sensible thing would be to mark his body and not take risks with anyone else, but I think Ken did not want to leave his friend, even if he wasn’t there to be comforted.

We jogged down the mountain. Looking back, it seems a miracle that neither of us fell. At the bottom we found a large, grey stone house. There were signs of life, but when we rang the bell there was no answer. We tried for a few minutes. I went to look around the garden and picked up a large rock.

“What are you doing?” Murray was half-confused, half-shocked.

“I’m going to break in – we have to get help.” I said the words with enough conviction to persuade myself. As I did a man appeared.

“What do you think you’re doing?” It was clear he thought he’d caught us in the act of breaking into his house – he had, but not in the way he thought.

We babbled an explanation and his doubt dissolved. We went inside to call the mountain rescue before being invited into the kitchen where we were offered tea and sympathy.

After an hour it was clear that the bad weather was back, and the rescue team said they could not go out while the weather was so bad. More hours passed and we filled the time speculating about whether John might have revived. I suspect that deep down we knew that it was hopelessly optimistic. We realised he’d been dropping things in a desperate hope that a lightened load would somehow make things bearable.

We worried what Ken must have been going through – stuck in another storm. I didn’t want to say to Murray – but I wondered why his father, a trained doctor, did not perform CPR. At my father’s funeral, decades later, he told me that he had worried that he would do more damage. I understood.

It was pitch black and deep into the evening when we saw Ken again. He was a man in shock. Because John had died so suddenly, I imagined something significant would be said or done, but instead everything was just so mundane.

We thanked the man for his help. Did I ever know his name? The car doors shut, and Ken drove us back to Stirling. If anyone spoke, I don’t remember it. The clearest memory of that journey is of watching Ken from the back, his face in profile, skin the colour of porridge, radiating sadness. I did not know it at the time, but after he dropped us off he had another task to do. He had to go and tell John’s widow that he was dead. That morning she had said goodbye – with no reason to assume she wouldn’t see him later that day:

“Life changes fast.

Life changes in an instant.”

I carried round the thought – no, the belief – that people would wrap me in a blanket of comforting words that would help make sense of the situation. None came. I have no recollection of seeing my parents afterwards. I do remember getting up the next morning to go to my pre-school job, stacking shelves at Marks and Spencer’s. When I tried to explain to Graham, my friend, he looked distinctly unimpressed, his tone dismissive. Then, when my shift was finished, the supervisor asked if, because it was the school holidays, I’d be prepared to do a few more hours. I remember looking at her as I tried to say I wasn’t sure I felt up to it because of what happened. Her hair was platinum blonde, scraped back at the sides with a pile of curls at the top. Her neck was craned forward, and head tilted to the side as she waited impatiently for me to finish my story. When I was done, all she said was, “Can you do it or not?”

I told her I couldn’t – and she walked away, unable to conceal her irritation. I was stunned that she could not see that this was a moment where a human connection was needed.

A day or two later John’s widow invited me and Murray to her home in Gargunnock, a village just a few miles from Stirling. She was the model of kindness and dignity – and pointed out that she could see Ben Vorlich from the sitting room window. I must have shown shock at this, assuming it would be a bad thing to be reminded constantly of where her husband had died, because she patiently explained that somehow it seemed right. I can see that now.

The funeral felt like it should have been a major moment, but it passed quickly and then it was as if nothing had happened. The lesson people seemed determined to impress on me was:

You just don’t dwell on death - because it’s too uncomfortable.

I’d looked to the adult world and assumed they must know what to say and do to make sense of it, when in fact, they were lost and frightened by the magnitude of things. Their tactic was to deflect or avoid.

I was thinking of John Bennett when I raised the subject with the BBC News presenter, George Alagiah, on my podcast, “Desperately Seeking Wisdom.” George had been cruising through life when he was confronted with a diagnosis of terminal bowel cancer. He agreed our avoidance of death was a major problem in our society:

GEORGE: There is something certainly around that we don't deal with death, I can remember in 1967 going back to Sri Lanka and my uncle dying, and his body being brought back to the house. And, as kids seeing this dead body there. It was a wake, and we don't do wakes anymore. I remember that wake so well because all the living people around this body, and mourning crying, laughing, shouting.

So, that body lying there was a kind of continuum, it wasn't something separate. This is a natural thing that happens, the kids can be there, they can see it all, because this is how it all ends.

We don't talk about death enough. Our medical system is geared up to intervene, intervene, intervene, but there does come a time when you need to have a gradual acceptance that actually death is coming, and that you have a choice about how that should happen, and I don't think we do enough of that. Cancer, of course, for me, has made it much more real, hands down.

CRAIG: It does mean understanding that you have been born into this order. This is the pathway, and I'm going to accept that that's the way things are and I'll probably be happier for it because I can't avoid it.

GEORGE: Yeah, that acceptance… you need to have those conversations so that acceptance becomes possible. We constantly treat death as this terrible shock. Oh, my God, so and so’s died. Actually, you know, it was going to happen…that can only come about by making it something that's not a taboo. And I think it probably still is a taboo in our society.

I feel odd publishing this piece. Hoping for engagement - expecting lower numbers than usual. Who wants to be bummed out thinking about dying?

Except there’s something unhealthy about not acknowledging and coming to terms with the inevitable. Ekhart Tolle says it is almost illegal to see a dead body in the west – and that is part of a culture that pushes away and refuses to accept reality. He – like so many other wise people - goes on to point out that death can be our teacher, if only we let it.

And that’s what I want to write about in my next piece – how truly accepting that we die, not just intellectually understanding it, can help us in so many ways.

I wonder: has anyone reached this point - does anyone want to read more about this most challenging of subjects? I’ll try again next week.

Notes:

The Year of Magical Thinking - by Joan Didion

https://www.joandidion.org/joan-didion-books/the-year-of-magical-thinking

George Alagiah talking to me on Desperately Seeking Wisdom

https://www.desperatelyseekingwisdom.com/episodesseries1/desperately-seeking-wisdom-with-george-alagiah

Hello Craig, we don’t know each other but George was a friend, and we often talked about death because my wife, also very fond of George, died from cancer a year or two before him. We used to bump into each at the London Oncology Centre! My point: there’s a big big difference between sudden unexpected death, which is rightly always shocking, and death where someone is terminally ill and sure to go, it’s just a question of when. My email is Christopher.wyld@ gmail.com.. ping me if you like and I’d happily send you a piece I wrote ( not for publication) after Kate died. All best, good piece!

Thank you Craig. An excellent piece