Desperately Seeking Wisdom

A new blog for people looking for guidance on navigating life in a complex world - with help on wisdom and mental health.

I am not a guru.

I don’t think I have all the answers – and I’m suspicious of anyone who claims they do.

In many ways the traumas I have faced are run-of-the mill – as nothing to those experienced by countless people around the globe.

I am a person who can see that there is an epidemic of unhappiness in society and was himself forced to confront the fact that his life was not working.

Radiohead’s song and video for No Surprises (an image of which is below) summed up how I felt:

“A heart that’s full up like a landfill,

A job that slowly kills you,

Bruises that won’t heal”

Robert Frost’s poem, Gathering Leaves, summed up the thought I had on my worst days, that everything is pointless:

“I make a great noise

Of rustling all day

Like rabbit and deer

Running away.

But the mountains I raise

Elude my embrace,

Flowing over my arms

And into my face.”

On an average day, life felt like a grind not a gift, and although I was outwardly successful, my emotional felt like a disaster.

I will always be a foot soldier, following the path others have forged. But what I’d like to share – as humbly as I can – is what I learned when I decided to see if anyone out there had the wisdom to help me find some meaning and live a more balanced and fulfilled life.

As I read, listened, and tried tirelessly, I found there are a lot of snake-oil salesmen, claiming they have discovered ‘The Way’.

But amid all that snake oil, I discovered there are some truly wise people – those who down the centuries have been clear-eyed about the reality of our existence.

They did not evade the fact that we live in a world of risk, where bad things can and do happen to good people, and good things happen to the bad. Crucially they were able to point to where there is solid ground, balance, contentment and even joy.

My conclusion was:

When we shift our perspective, it becomes obvious that life is a gift, no matter its trials.

I also learned that when I was open about how I had struggled and was willing to be vulnerable with others, it helped people speak about their own pain or shame. Where they had often hidden it before, they now opened-up, petal by petal, like a flower being exposed to the sun.

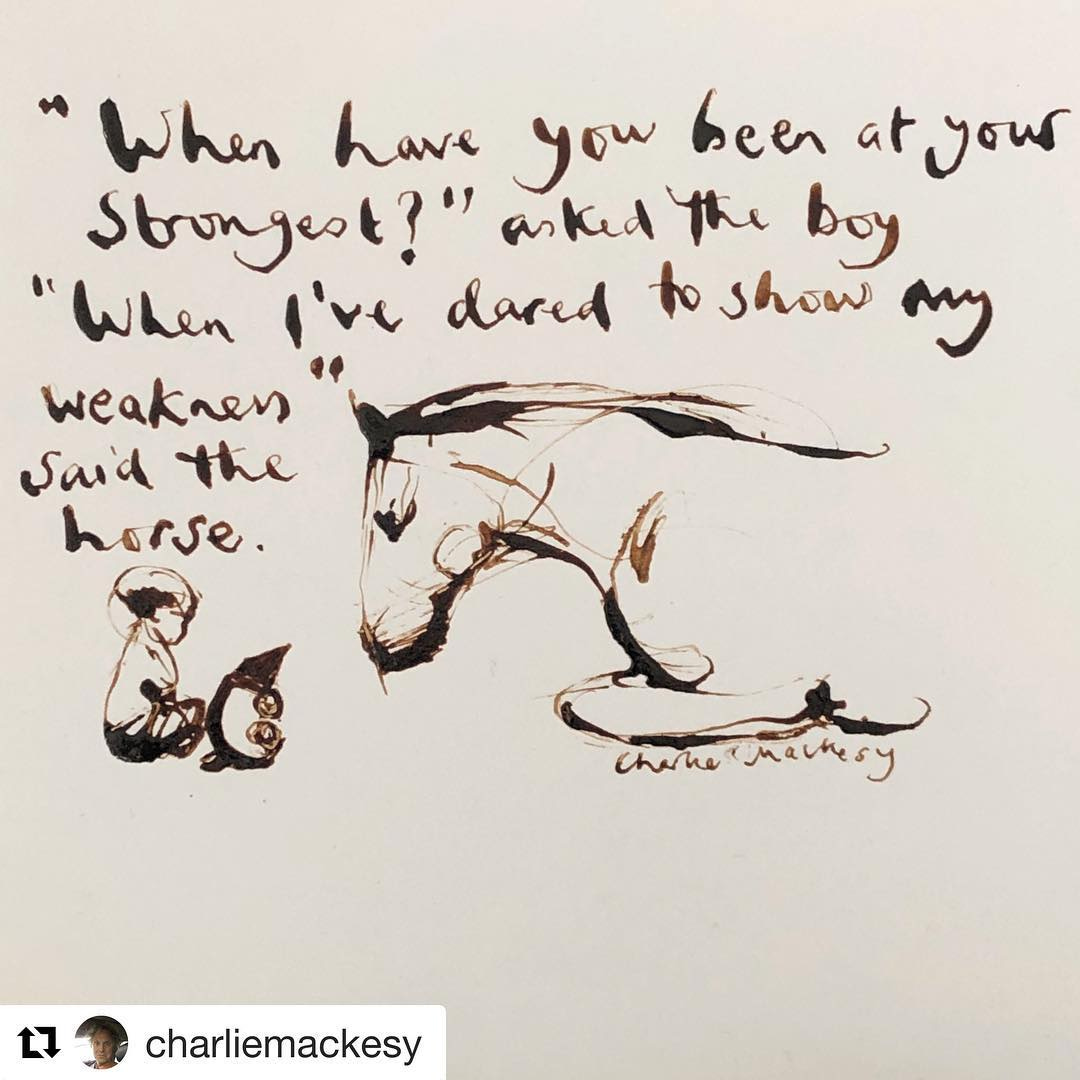

The vulnerability of others has helped me, and I hope sharing mine in these posts will help more people. This short conversation from Charlie Mackesy’s beautiful and direct book, “The Boy, the Mole, the Fox and the Horse” nails this point:

I hope that by being vulnerable others may feel able to open-up – and I might point them to what helped me.

You’ll discover I endlessly refer to books, music and films as a way to illustrate my points. So here are some Crowded House lyrics from, “Don’t Dream It’s Over”:

“There’s a battle ahead,

Many battles are lost,

But you’ll never see the end of the road

While you’re travelling with me.”

That sums up what is a key piece of wisdom for me:

Making sense of life will be a process that doesn’t stop. There are peaks and troughs, apparent wins and losses; but by focusing and being open and engaged, the trajectory of our lives is likely to be upwards. The effort won’t stop. We will continue to get things wrong - but there will be fewer mistakes and we will at least be headed in the right direction.

How and why I came to write this blog…

The journey to writing this began just before the first Coronavirus lockdown. It was a few days before Christmas and – yet again – I found myself under intense pressure. A client suddenly insisted that we re-bid for their contract, with a deadline of January 2nd. It meant the holiday period would be blown out of the water – with me having to produce an ultra-high quality, fifty-page document in under a fortnight. Accepting the task and not pushing back wasn’t unusual for me. As someone who had edited BBC TV News programmes and then gone on to become Director of Politics and Communications at No10 Downing Street, I was used to sacrificing what should be precious down time in the face of a punishing deadline.

To add to the strain, the person I believed I wanted to spend the rest of my life with decided to end our relationship in a way that felt brutal, selfish and cruel. They had their reasons, and I suspect they didn’t have the emotional tools to articulate them, but the effect for me was like turning suddenly, seeing an oncoming train and knowing there was no way I was going to be able to jump to safety.

A year before I had decided that although we loved each other, we could never make each other happy and said we needed to separate.

But over the next ten months, she campaigned to come back into my life, insisting she was ready for serious commitment. Uncertain – not least because she had told me in a rare moment of frankness that it was in her nature to sabotage relationships - I relented. My only condition had been that if it was to work, we both had to be all in. She agreed – only for me to find from the re-start that she was anything but. After ten of the unhappiest weeks of my life, where I accepted the unacceptable because I had convinced myself being unable to make it work would be a cataclysmic failure on my part – she did what she had warned me: sabotaged the relationship. It was three days before Christmas.

Again, private turmoil was not unusual. I had lived with it many times before. But something was different this time. The cracks were starting to show.

I managed to keep it together – not letting others know, finishing the document and winning the work. But I was a mess. This was clearly about so much more than the work and the break-up. I had not resolved problems that stretched back into my childhood and these events were merely triggering an inevitable moment of reckoning that had been staved off for too long.

I realised I had built a dam to hold back decades of pain and poison. The added pressure from these events was now enough to smash it into a thousand pieces.

My system flooded with adrenaline and cortisol. The effect was to leave me in a constant fight or flight mode. When I wasn’t working, I sat on my sofa persuading myself that this was my lot in life - condemned to fail to connect.

When I spoke to my therapist - who I had re-engaged a couple of months earlier to help me deal with the consequences of allowing my partner back into my life – I described the pain as being physical, like having a jagged lump of granite wedged under my rib cage, leaving my heart bruised and aching – and no amount of tears that poured out of me when she asked, “How do you feel about that?” would ever dissolve it.

I prepared meals I could not eat. The weight fell off me. Sleep for more than a few hours became impossible. I would crash out exhausted at the end of the day, only to wake in the small hours with my mind a riot of thoughts. I couldn’t see a point to anything and even asked myself if the oblivion of death would be preferable to this.

Never one for fitness – I had to try to control the surge of energy. I felt driven out into the icy darkness to run hard and fast from my west London home, up and down the Thames. One morning, I tripped and did not realise I’d cut my hand. I noticed the odd person I came across looked at me with a mix of worry and fear. It was only when I returned home that I realised my face was a bloody mess. As I had been wiping the sweat off my brow, I was smearing on blood from my cut hand.

When lockdown followed soon after, I saw an opportunity. With more time on my hands, I could use it to sort myself out. As well as getting fit, I was going to read and listen voraciously.

Could I find any wisdom that might help me live a life that was more balanced and centred? Why had my work life been a success, but my emotional, private life such an unending struggle? Why had some of what should be the foundational, primary relationships in my life been broken, or failed?

Much of what I encountered felt glib and exclusionary. Some writers wanted me to check my brain in at the door as they described “woo-woo” fantasies or hoped I would buy their merchandise with bitesize pieces of “wisdom” that could fit on a fridge magnet or a t-shirt.

But others seemed to point the way to a simpler, better way. It became clear to me that so much contemporary psychology shares the insights present in ancient texts, many of them eastern. I started to understand that I need not be a slave to my thoughts and feelings. If I slowed down and learned to respond and not react, life became clearer. I fought with and finally understood and embraced the concepts of surrender, acceptance, and gratitude (major areas I will return to in more detail).

As I continued my morning runs and broke up long lockdown days with walks in nature, I saw that a tree looks pretty much the same tomorrow as it does today – but that with the progress of the seasons, it will be changed utterly. It became clear that there is a way to things that tends to be slow but insistent. We can try to force or control the world – as I had done so often - but too often that can leave things bent out of shape and people resentful, and it would have been better to have had more understanding of when it was right to resist and impose myself, and when it was not.

I started to see a pattern:

A thing doesn’t exist;

it comes into being,

it gains momentum and peaks;

then it starts to fade;

finally, it no longer exists.

When I thought about it, that pattern applied to everything. Our lives, nature, relationships, objects, the planet. In fact, the entire universe follows that cycle. And what was clearer than anything was everything - everything – ends.

Thinking this way helped me see that I had been taught and learned the wrong lessons – not least that a frenzied effort to achieve might somehow concrete over my deeply unhappy childhood, with a mother with a personality disorder and a father who too often felt like her enabler, unwilling or unable to protect me, my sister and my brother.

When I stood back, I saw that all my efforts were the equivalent of commanding a fleet of mechanical diggers to make beautiful and elaborate sandcastles on the beach. At the end of the day I would survey my achievement for a moment, before realising the tide was coming in to wash it all away.

For too many years, my response was to get up the next day and repeat the process again. The endless repetition while expecting different results was – as the saying goes – the definition of madness.

The poet Philip Larkin had always made a lot of sense to me. He observed our pain like few others - but I came to realise that although he was a genius at describing the disease, his belief there could be no relief from it was wrong.

His final masterpiece, ‘Aubade’, takes its title from a type of poem dedicated to the joy of waking up in bed with a lover. Typically, the writer finds ever more playful and elaborate ways to insist that love can conquer all. A famous example is John Donne’s “The Good Morrow” which concludes:

“If our two loves be one…none can die”.

It’s an assertion that romantic love can beat death. In this light, Larkin’s title is bitterly ironic, going on to describe himself not waking with a lover, but close to death.

It is an extraordinary, evocative piece of writing. The imagery captivating. The internal logic devastating. And it contains the most profound insights into the human condition, including:

“An only life can take so long to climb

Clear of wrong beginnings and may never.”

This view is echoed by contemporary psychologists who are discovering more and more about how the templates of our lives are set very young – in our first weeks, even in the womb. Neural pathways are created that help set and restrict our behaviours and thinking. The effect is like a boat starting a long journey a degree or two off course and ultimately finding itself thousands of miles from where it should be.

That is how I felt, failing to understand how I had ended up so far adrift. My “only life” had resulted in me ending up as a fifty-year-old man, all at sea, with no means of finding a route to being content.

And yet while Larkin’s diagnosis of the human condition is devastatingly precise, his ideas for a treatment plan are woefully inadequate – abandoning us with the kind of wisdom you might find on a painfully unfunny bumper sticker: Life is a fatal disease.

The poem itself succumbs to assumptions and logic that are so endemic in our culture, and as a result, fails “to climb clear of [its own] wrong beginnings”.

In starting from the belief that the mind and the ego are all, Larkin cannot help but be tortured by the idea that one day they will be extinguished, facing “unending death.” Rather than choosing to accept the gift that he is conscious on a planet that is the most beautiful in the known universe, full of wonders, he sees his life as almost worthless, like so much toilet paper, “torn off unused.” Such thinking condemns him – and us - to the nihilistic conclusion that life is a kind of sick, cosmic joke, the punchline being, that it is all pointless, we cannot make sense of it and the resulting discomfort and finally fear on facing death paralyses us.

For so much of my life, I also succumbed to this kind of logic. It is all pointless, until I started to wonder if I was looking at it all the wrong way.

In an earlier poem, Larkin delivered his most famous quote about how we are often set of on the wrong course when we are young:

“They fuck you up, your mum and dad,

But they were fucked up too.”

It’s a funny couple of lines popularised by their gleefully blunt obscenity; but for me, Larkin offers something far deeper a few verses later:

“Man hands on misery to man,

it deepens like a coastal shelf…”

In other words, we are often victims of victims. The slow grind of unhappy people passing on misery to others is the blight of millions, even billions, shaping our culture and psychology over generations. I started to think that as I considered my deeply unhappy childhood, that if I had been a victim, then so too had my own mother. Her father had been an abusive sociopath who had sent her spiralling off in the wrong direction. And if that was so, how much responsibility did she have for her own shocking behaviour? Did she deserve to be let off the hook because what happened to her distorted her so much that she was incapable of showing a mother’s love, inevitably “fucking up” her own children? Or was that too easy? Freeing people from responsibility for their destructive behaviours? Did any of this kind of thinking help?

I realised I probably would not find an answer, and was reminded of the line in, “Paradise Lost”, when the angels, cast out of heaven, sit on a hill, considering,

“Fixed fate, free will, foreknowledge absolute,

And found no end, in wandering mazes lost.”

As if by way of a solution, the concept of acceptance started to loom large in what I read, and I will spend some time in further entries trying to explain why it is so crucial to seeing things differently – and ultimately liberating us from so much turmoil.

Around the same time, I was encouraged in therapy to describe the image that came to mind when I thought of myself as a young child. Instantaneously, I was about four years old. I had a cheeky but uncertain, rubbery smile. The brown polo neck I wore was very 1970s, and the image of a native American on a horse embroidered on the bib of the beige corduroy dungarees seemed painfully innocent. As I described the photograph, I started to cry uncontrollably. A waterfall of tears appeared as if from nowhere.

This little boy didn’t deserve what happened to him. He paid a heavy price for it, skewing his view of the world – eventually following rules to live by that did him no good; thinking that if he just worked hard enough, he might be freed; or out there was someone who might make make it all better, make him happy. No one taught him to think that he was loveable or enough. The wrong course had been set for him – and how the man he became would have to try to reset that course.

Thinking about it I realised how we have become so used to viewing and critiquing things through social, political or economic prisms, we might get just as much insight from looking at things through the lens of psychology.

More to the point – we have become used to rejecting or even ridiculing a spiritual view of things. My fingers hesitated above the keyboard before I typed the word “spiritual” – fearful that I would immediately be accused of losing the plot or trying to ram some outmoded and ultimately harmful approach down your throat.

Let me be clear – I do not know if there is a God. I’m not sure, but I doubt consciousness survives death. The theory that the purpose of life is for the soul to evolve strikes me as a lovely idea, but can’t be proved. But there is something in us we call a spirit, and it becomes weak and shrivels if we fail to nurture it.

So many of us have a hole inside of us – and consciously or unconsciously we are engaged in the task of trying to fill it. Many are fooled into thinking we might do it through drink, drugs, sex, workaholism, controlling behaviour, narcissism, co-dependency…any number of destructive approaches that allow us brief moments where we are entirely present, only to pull the rug from beneath us and leave us feeling worthless. Others can exist in a kind of sleep state, where the days roll into months and years and we are left wondering what we have to show for any of it.

In writing this blog, I have picked up the themes and questions that arose as I attempted to find the wisdom to understand where I have come from, where I am going – but most importantly: How just to be - free of anxiety and too much expectation.

This Substack feels like a risk. Putting myself out there. But it’s my hope that by being vulnerable it might help a few other people to shift their perspective and see:

Life isn’t a trial to be endured – it is the most extraordinary gift. It may all end - but we should be grateful that we get to experience it, no mater the trials and tribulations.

I will explore that thought more deeply in next week’s blog.

Notes:

“No Surprises”, Radiohead

“Gathering Leaves”, Robert Frost, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/148658/gathering-leaves

“The Boy, the Mole, the Fox and the Horse”, Charlie Mackesy, https://www.amazon.co.uk/Boy-Mole-Fox-Horse/dp/1529105102d

“Don’t Dream It’s Over”, Crowded House,

“The Good Morrow”, John Donne, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44104/the-good-morrow

“Aubade”, Philip Larkin,

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/48422/aubade-56d229a6e2f07

“This be the Verse”, Philip Larkin

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/48419/this-be-the-verse

“Paradise Lost”, John Milton

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45718/paradise-lost-book-1-1674-version

This is really beautiful Craig. Painfully honest and evocative. It reminded me of a quote from Anne Morrow-Lindbergh's book Gifts from the Sea; 'the most exhausting thing in life is being insincere'. Keep writing and sharing!

Thank you, Mary.

I really appreciate such lovely feedback.

There’s another blog dropping Sunday.

Do let me know what you think. And of course share with others 😀